An Embarrassment of Riches

(A More Complete Draft)

By Dana Southworth

Note from Black Cat Prose: the following is a work in progress of a book about the Garland Mill in Lancaster, NH by my good friend Dana Southworth.

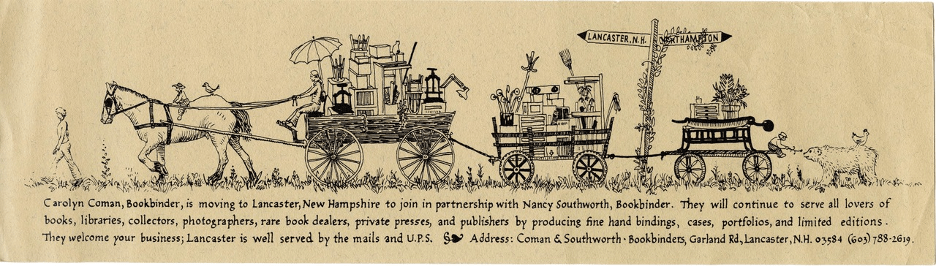

Pencil sketch by Robert Wójciak

This book is dedicated to Harry and Tom Southworth, 5’-6” giants upon whose shoulders I attempt to stand every day*; and to my wife Izabela – her move to the end of this wagon trail 20 years ago made such a rambling reminiscence possible.

Dana Southworth

Lancaster, NH

Winter, 2023

* More about these fellows in the Afterword(s) by Joel McCarty

Contents:

Forward – excerpt from Yankee Magazine December, 1973 (Judson D. Hale, editor)

Preface – Sort of A Northern Saga (ref. Bill Mauldin)

Introduction – The Tail Wagging the Dog

Chapters

1) When Flatlanders Bought The Mill – Starting in the middle of the story

• Yankee advert becomes a reality

• Wives wanting out (of the rat race)

• Brass nuts and horse logging

• The Peanut Gallery and benign poverty…con’t. in Ch. 4

2) Learning from Harold Alden and his Predecessors

• Harold’s visits: “you boys must be sawing wide pine”

• Flat belts and babbit bearings; the genius of the contraption

• The Repo’d edger and other curiously productive machines

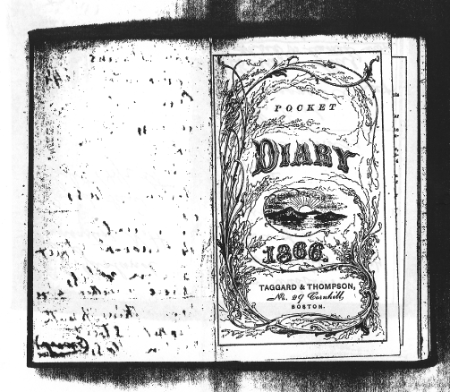

• Eben Garland’s 1866 Diary – are we chronologically egotistical?

3) The Garland Mill Over 17 Decades: 3 Sets of multi-generation family stewards

• Garlands – 19th century big timber heyday, then off to Tennessee

• Aldens – Every good farm needs a sawmill, and vice versa

• Southworths – Raising pigs and timberframes; out of the frying pan and into the fire

4) How Tom and Harry Saved the Mill – resuming the tale a decade later

• Romanic notions, thin margins, good times

• Hydro power as harbinger of change

• There is a pony under all this manure: the improbable rise of Garland Mill Timberframes

• 1st generation business and the “Southworth Family Employment Agency”

5) Gen X Tests the waters, and their Dads

• “We want to be carpenters not businessmen”, then the big buyout

• Saddling the green steed – rebuilding the water turbine and super-insulated homes

• Loss of Fathers, not of purpose

6) What’s Next and What’s at Stake?

• The relevance of such an endeavour

• Caretakers by job description, owners by default

• Another generation in the mix?

Afterword(s) by Joel McCarty: TFG Director’s Sendoff for Harry and Tom

Timeline and Synopsis of 168 Garland Years

Cast of Characters: An incomplete, but growing list…

Reprint of Coos Co. Democrat article about The Garland Mill from May, 1983

From Tree to Timberframe: A Unique Process (photo essay by Fletcher Manley)

Endpiece – Looking Back to Discover the Future

Reference List

Foreword – This excerpt from Yankee magazine sets the stage for our adventure as well as anything I could have imagined; and resulted in our family taking on stewardship of the Garland Mill.

Citation: Hale, Judson D. (1973). Garland Mill Forever. YANKEE, Monthly Vol. 37 No. 12 December, page numbers 34-38.

House for Sale. Yankee likes to mosey around and see, out of editorial curiosity, what you can turn up when you go home hunting. We have no stake in the sale whatsoever and would decline it if offered.

Would you know how to find a Christmas present that would make about half the men in this world happy – i.e. truly happy… i.e., permanently happy? Well, here’s how:

From U.S. Route 2 in Jefferson, New Hampshire, take North Road towards Lancaster. After going a couple of miles, you’ll come to Gore Road, a side road to the right – actually the first side road. Follow Gore Road for a mile or more to an abrupt turn to the left, where it becomes Garland Road. At the foot of a gentle hill, not half a mile on, the road crosses Garland Brook. Stopping here, you may look downstream across a meadow punctuated with balsam firs to a millpond and, beyond it, to the last of New Hampshire’s water-powered sawmills that operates for profit. Now look up the road at the edge of the meadow, to a white house with porches on both sides. Turn around and see the view of beautiful Mt. Cabot and the Pilot Range that the house sees. And there you have it: an operating water-powered mill which has supported Harold Alden, the owner, for 47 years; a five-room house (with complete bath), built in 1929 with lumber cut and sawed by Alden; seven acres with the book, millpond and view; plus innumerable out buildings including an old blacksmith shop, complete with forge and anvil; two garages (both two-car); tool and wood sheds, etc.

The Mill is three times bigger than it was when built in 1856, but the original, timbered frame, complete with rafters and ridgepole, is enclosed by the present building. An 18’ saddle on a Lane Triple Aught carriage can feed 32’ to 34’ logs to the saw. A bullwheel drives the endless chain which draws the logs from the millpond while a slab saw is rigged to cut the slabs. To dress out the finished lumber, there’s a 24” planer that can handle timbers 12” thick. A two-saw gang edger finishes boards up to 18” wide. A tongue and groove machine mills matched boarding to 12” widths. Finally, there is a 6” clapboard planer.

All of the equipment is powered by Garland Brook. So, phooey to the “energy crisis!” However, to be perfectly honest, there are times when the Garland Brook says phooey to the mill. During dry spells in the summer, for instance, Harold Alden is accustomed to begin sawing at 4:30 A.M. until the millpond no longer has sufficient water to drive the saw through the log. Then, later in the day, after the pond has filled again, he will saw into the evening.

Yet despite the vagaries of water-power in the seasonal operation of the mill – April through November – Alden saws between 150,000 and 200,000 board feet of softwood lumber annually. Of this, about 50,000 board feet is custom-sawed for people who bring their own logs to the mill. The larger balance is sawed from logs that Alden buys for his own account and, after sawing and planing, sells retail at the mill to customers to come by. In addition, there are approximately 300 running cords of slab wood (figure four “running cords” to one regular or solid cord since slab wood is sold in foot lengths) produced and sold in a year.

One more thing you ought to know about the mill – particularly if you are asking directions. It’s the Garland Mill not the Alden Mill, even though William Alden, Harold’s father, bought it from the Garlands 88 years ago. Old names aren’t easily changed in the country. (There is an Alden Mill about a quarter of a mile away, but that’s a diesel-powered mill run by Harold’s brother.)

Harold is not particularly happy about selling this property on which he has lived for more than 70 years; but then, nobody is particularly happy about some of the decisions that are dictated by advancing years. He was even reluctant to talk price although he finally allowed that the house, land and mill “should fetch nearly $50,000.”

So you can take it from here. His address is simply Lancaster, New Hampshire; phone 603-788-3597. If it all works out, just remove the pages of this article and put them into an envelope on which is written the name of the luckiest man in the world. Then add four words: “It’s yours. Merry Christmas!”

Harold Alden opening main sluice gate to start up the mill in the early 1970s (Photo: Robert Morey)

Preface – Sort of A Northern Saga (ref. Bill Mauldin)

The rural paradise of northern New Hampshire was clearly a childhood mirage, as seen from my 10th floor office in Washington DC. When we moved back there some years later imagine the surprise and delight, almost incredulity, that it was not a figment of the imagination. In fact Lancaster and Coos County, NH were remarkably the same as had been almost 20 years prior when I took off down the road to find something important in the wide world, though that something now escapes me. The mill was also still there, perched on the edge of the pond, gazing benevolently up at Mt. Cabot and the Kilkenny basin watershed that sustains it.

The Mill has always been more than just a name or even a proper noun to me, rather a way of life from earliest recollection. Other than extraordinary grandparents, the only thing I remember acutely from the first half-decade of life (1971-76) were visits to this magical place inhabited by cousins Ben and McGowan. By the time my folks moved up to join the fray several years later I already had a number of key moments seared in my memory: watching Dad and his brother Tom hand-dig and frame a hobbit-like structure into the earthen bank below the pond, which turned out to be a sod-roofed sauna; and getting stranded midway across the 6” wide catwalk over the mill dam, frozen by fear and indecision until my father hollered down from the house “just don’t look down”.

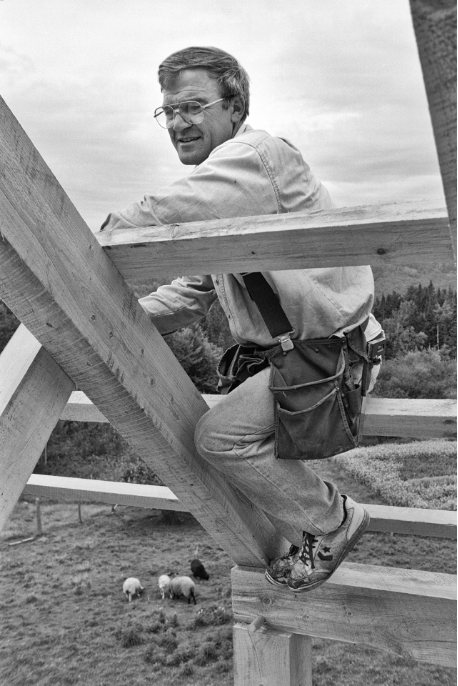

Author in retreat from earlier bureaucrat days, sawing 19th century style. (Photo: Matt Hammon)

Family gatherings, Summer Solstice parties, weddings, funerals, birthday celebrations took place by the stream, in close proximity to the mill. Baseball skills and hockey moves were honed on the adjacent field and log pond. A fair amount of child care was also enacted within the mill – as urchins we were directed to stay put in the peanut gallery (a small platform next to the log deck that conveniently held 4 kids) while our fathers sawed and kept an eye on us. From the vantage point of growing up in the village of Lancaster, about 6 miles WSW of 214 Garland Road, any social visit or after school bus ride to my cousins’ house was considered “going out to the mill.”

My mother Cid and aunt Nancy were in many ways the glue that held the operation together or at least tethered to terra firma, but observing my father and uncle’s vocational antics left a rather more dramatic impression, and are the main foci of this little book. I use the term antics with some reservation in that Harry and Tom Southworth were two of the most intelligent, focused and non-frivolous men I have ever known. Their work as with their love for family embodied concentration, sincerity, and a real spirit of adventure.

In setting out to chronicle some of what happened at the Garland Mill over the past half-century, and shed light on previous doings at this 168 year-old agro/industrial complex, I’m sifting personal experience through several filters: narrative, visual and literal. The former comprising events actually witnessed or heard telling of on good authority; the latter via reference to the many books read aloud by wonderfully free-range parents, aunts, uncles, etc. (and the few I managed to get through on my own). In particular Bill Mauldin’s recollections of growing up on the whip end of familial adventure in no holds barred 1920s New Mexico, as presented in A Sort of a Saga have resonated ever more profoundly since the time(s) my father shared them with us as kids. Back in New Hampshire I paid the hilarity forward to my own sons at bedtime, and often wonder if there was something similar in the water at these two North American antipodes. Real or perceived, the experience to date has been what Uncle Tom would joyfully have proclaimed to be an embarrassment of riches.

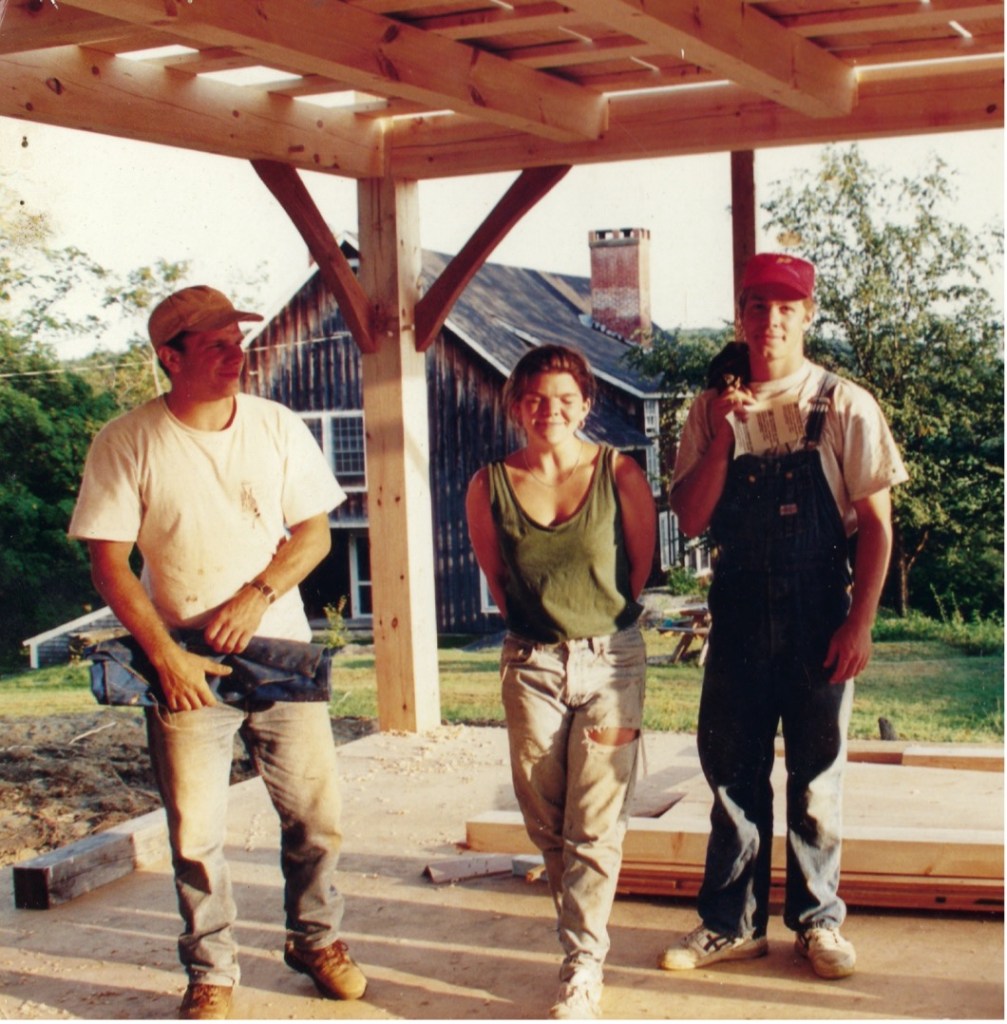

Author by millpond with Tom (uncle) and Harry (father) – summer 1994. (Photo: Polly Pike)

Introduction

As the 9-ft.-long yellow birch lever is pulled down, there’s a sound of water surging through the penstock into the wheelpit. Then a few thumps and knocks and the straining of belts. The board saw advances weakly and the edger stutters, then springs to life. As more water drives across the canted fins of the turbine the mass of iron spins faster, and the floor, in fact the whole building, begins to rumble and shake. The mill comes to life again.

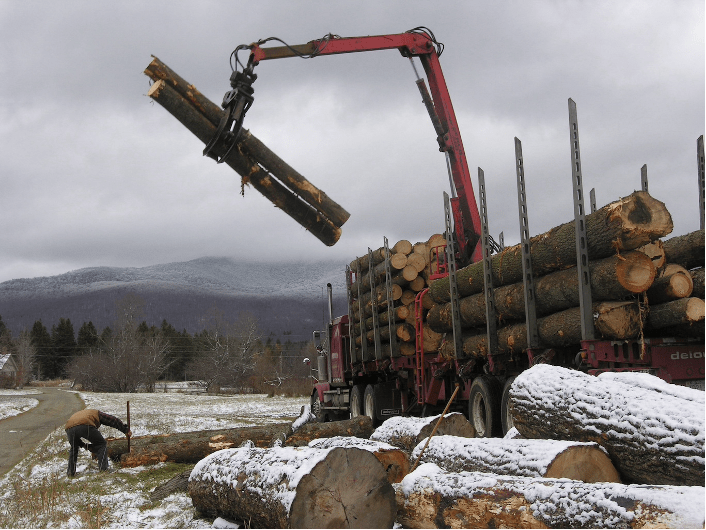

The Garland Mill is a curious specimen–a small sawmill, still powered only by water and trying to stay relevant in this era of laser-guided bandsaw mills, 3D structural printers, and artificial intelligence. It’s also the pre-Civil War cornerstone of a family-owned timber framing business. The Garland Mill, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, has been in continuous commercial operation since it was built in 1856 in far-northern New Hampshire, and produces timbers and boards pretty much in the same way it did five years before Abraham Lincoln became president.

Directing traffic on the millpond with a sharp pike pole and good balance. (Photo: Fletcher Manley)

Three sets of multi-generation family owners (Garlands, Aldens, Southworths) later, the mill is still rumbling, creaking and whirring with productive zeal. An estimated thirty-two and a half million board feet of lumber and timber have been sawn by water power over the past 168 years. Same analogue machinery, same stubborn determination, same seasonal operation at the convenience of Mother Nature.

It might be argued that the 1850s sawmill is actually the tail wagging the dog. Sitting astride the stream that is also harnessed to generate electricity to run table saws, planers, etc. in the adjacent shop, the mill remains the heart and soul of the in-house timber frame business. It has supplied numerous hard-to-source specialty timbers, helped sell a job or two, and captivated the imaginations of many of us, grateful for the opportunity to live and work in dramatic proximity to nature.

Not only a great and good sequestration of carbon per modern parlance & fascination, but more importantly an extended tenure of resource conservation spanning the arc of Garland Mill operations. The long-enacted practice of “upstream green” * that here epitomizes Yankee sensibility and frugality has resulted in quite a run of healthy and lasting wood-products. The strong and sustainable end result: houses, barns, pavilions, furniture, garden beds, etc. sprinkled across the North Country (and beyond) are bearing up well with clean bills of material, and conscious. Locally logged trees, milled with no environmental degradation, and near full-utilization of the “waste” products (sawdust, kindling, mulch) sets this operation apart historically, environmentally and logistically; yet begs a host of other questions and conundrums to be tackled as we forge ahead.

After making some initial headway in the effort to write a book about the Garland Mill, friend and intrepid photographer Tom Wilson asked the seemingly innocuous question “Why does this place still exist?” Simple, I blurted out, because it has always been powered by water. Sawmills and sparks don’t always place nicely together. Whether via steam (generation), diesel or big electric, the comingling of internal combustion and sawdust has been the fiery demise of many mills.

The easy and apparently conclusive answer to Tom’s query, however, did not fully satisfy me, nor likely him. Why does an 1850s anachronistic contraption of flat belts, wooden pulleys and aged blades still attempt to operate commercially when nearly all of its peers are on permanent vacation or burnt to the ground? A more complete and convincing answer was not right at hand, but my curiosity had been piqued.

If not only fire as a suitably destructive option, why haven’t floods washed the operation away? Well, that’s been at least as threatening to the old mill on the banks of the Garland Brook – a tame rivulet most days but a raging torrent after heavy rains. One that often gets me (as it did my predecessors) out of bed and onto the dam pulling boards off at 3:00 a.m. in a desperate effort to lower the water level. Or possibly the unique efficiency of the water turbine and perceived savings on fuel costs? Yes, nearly seventeen decades of continuous operation without buying one cent of fuel oil has put some proverbial pennies in the pocket, but there is another side of the ledger: not insignificant labor costs to run and maintain a sawmill like this one.

Is there more to the story than technology, tactics and a dose of good fortune spanning three centuries? Likely so, but it’ll take some poking around and musing coherently in a semi-detached manner to unearth additional, compelling reasons. In fact, this provokes a similar sensation as when a school group or history buff comes out to visit the mill, and almost always gets a working tour of the place. While explaining the various aspects of converting hydraulic to mechanical force, antiquated power transmission, and the intricacies of a hand-set rack and pinion drive carriage, it again dawns on me that there is something a bit unusual about this set up.

Having grown up in and around the mill it seems normal and only reasonable to cut lumber in such fashion. I don’t take any of it for granted, but the place, process, and product are very familiar. Hence the surprise, then recognition that Tom’s question was a reasonable one. Maybe even closer to the bone that I was ready for, but nonetheless in need of a thoughtful answer. Please bear with me over the following pages as I attempt to explain what has been going on here, and tease out a bit of meaning, or at least some compelling detail from the Garland’s, Alden’s and Southworth’s 168 year-long stewardship of The Garland Mill. Onward!

* The moniker “upstream green” calls out the entirely clean energy input (unadulterated flowing water) for the main aspect of production at the Garland Mill, which is sawmilling timber; and differentiates this from other post-production (downstream) environmentally friendly efforts – lithium power batteries, spray foam insulation, solar panels, etc.

19th century conservationist pragmatism is still churning away in East Lancaster, New Hampshire.

Chapter 1.1 – Yankee advert becomes a reality

When inquisitive people make unusual decisions without an overabundance of caution interesting things can happen. Particularly when fame and fortune are not key ingredients, yet risk and hard work are “givens” in the equation. Such was the math in 1974 when my uncle Tom and aunt Nancy purchased a homestead with accompanying water-powered sawmill in the forested uplands of northern New Hampshire. A well thought-out, though nonetheless bold decision that put our family on a unique trajectory that we are still charting, and being rewarded by, half a century on.

Southworth family lore has it that Tom’s sister-in-law Bessann Triplett gave him a copy of the Yankee Magazine For Sale article about The Garland Mill shortly after it hit the streets, telling him that such a place might channel some of that boundless energy. The Triplett’s colonial timber framed home in Francestown, NH seemed the perfect jumping off point for such an adventure.

Tom was one of at least 100 proclaimed suitors for the Yankee prize, some few it seemed interested in keeping the small, seasonal sawmill going as such. This was apparent to Harold Alden—owner, operator and steward of the enterprise. As potential buyers mused aloud on the location of the new gift shop and streamside lounge, the prospect of a sale mysteriously diminished. The “flatlander” from Philadelphia, however, was audacious enough to actually try to learn to run the mill, sleeping in the equipment shed for weeks at a time and meeting Harold at 5:15 each morning to get started.

It was enough of a curiosity that half-brother Clayton (Alden), who ran a mill of his own just down the road, would stop by and observe the vocational instruction. Tom got the hang of things quickly but realized one afternoon that he’d asked enough questions about the different species of logs they were sawing when Clayton dryly replied that “yes, this might be a spruce log but it was cut from a hemlock stump.” Back to work stacking boards, sharpening the saw and repairing late 19th century equipment. Some time passed and then the deal was done and Judson Hale’s advertisement prophecy fulfilled.

More will be said and shared on this topic, including additional family stories and recollections, letters of encouragement and caution, and at least some of the facts…

Not long after Tom, Nancy and infant son Ben moved into the barn (and months later) the house by the millpond it became apparent that running a sawmill was a team sport. Nancy’s work spirit was (and remains) indominable but her bookbinding hands were way too valuable to be consorting with whirring swing saws and flapping belts.

Will Decoursey and Dave Craxton were Tom’s first employees, and each worked for a season of spring sawing. Will’s wife Nancy, upon delivering a lunch during that first year of new arrangement commented “So, you do make something other than sawdust here”. Benevolent cynicism possibly, though words we still keep in mind.

Tom had been enticing his younger brother Harry to also leave PA, and bring wife Cid and young son and daughter to join the new, inspiring life of hard work and little pay in Coos County…

Chapter 1.2 – Wives Want Out (of the rat race)

Though Harry and Cid (my parents) died before I had the chance to get the un-redacted story on their move from State College, Pennsylvania to Lancaster, NH, there is sufficient anecdotal evidence to stitch together a plot. And with Aunt Nancy’s corroboration, the motivations appear to have been rather straightforward. She and Cid recognized in the old sawmill and particularly in its environs an attractive alternative to the suburban bliss each family was comfortably mired in. Nancy’s bookbinding aspirations, which are the makings of at least another book or two, brought her into contact and collaboration with a Vermont printmaking artist. The partially tamed countryside and sparse populations won the day, and her husband was up for the adventure. More detail in the Afterword by Joel McCarty.

Little time was lost before visitations, negotiations and relocations were on the front burner for my folks. Though contentedly ensconced in his research work at Planning Studies, a Penn State-affiliated think tank, Dad was not immune to the charms of northern NH or to the inclinations of his wife. Mom grew up as a Navy “brat”, living in far-flung places–Malta, Liguria, Newport News, VA; but always considered central Vermont to be her home. Generations of McIntyres, the maternal line, had lived there since emigrating from the Scottish Highlands many generations prior. Hence the move to Lancaster in early 1977 with 5-year old Dana and 4-year old Georgia, a carful of cats and other belongings, and not too many trepidations of what lay ahead.

Not until attempting a similar move at a similar stage of life—2004 relocation from Sarajevo, Bosnia did I more fully recognize the courage and determination of their endeavor (we returned to the antique sawmill, by that time enmeshed in a small, yet solid timber frame building business and plenty of familial and community support). They, as had Tom and Nancy, plunged headlong into a tantalizing, yet unplumbed void. Ideological, rather than economic or political migrants seeking a more fulfilling way of life.

Illustrated commentary by Lance Hidy (c. 1977) well captures the mood of the day.

Neither Tom and Nancy nor Harry and Cid were hippies or “back to the landers” per se; however their lifestyle and broader sensibilities shared many complimentary tenets. Rural New England was, and largely remains, a place where inspirational work/life notions bolstered by serious work ethic can yield satisfactory results. This was understood and exemplified by new friends they met upon arrival, many of whom were drawn from afar into the Stinehour Press orbit—Stephen and Paula Harvard, Lance Hidy and Carolyn Coman (Nancy’s bookbinding partner), and other conscientious creators making lives of their own choosing “North of the Notches”.* All romanticism, or at least some of it, aside, this new arrangement was going to require compromise, and a hell of a lot of hard work to get off the ground and keep aloft….more to come along this line of thinking.

* The towns, villages, granges, gores, and real wilderness that lie to the north of Franconia, Crawford and Pinkham Notches, the geological gatekeepers of this secluded realm.

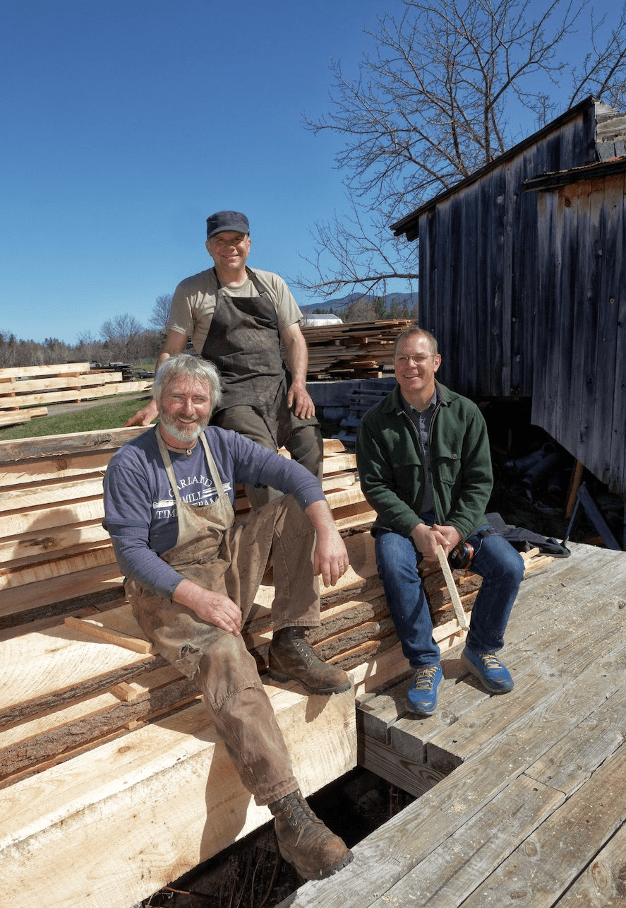

Matt Hammon (left) with Dana and Ben Southworth after a spring sawing run in 2016. (Photo: Fletcher Manley)

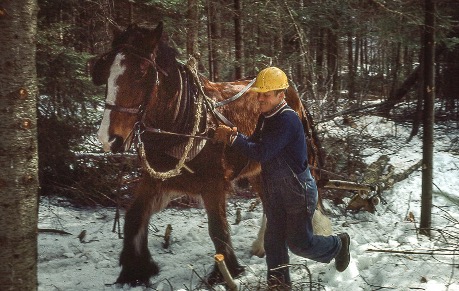

Chapter 1.3 – Brass nuts and horse logging

Following the initial Southworth migration north, inspectors soon started to arrive. Long-time friends from Philadelphia, Paul and Ann Haslanger drove up to see for themselves the madness that Tom and Nancy had signed on for. An engineer by training and mindset Paul immediately sized up the sawmill along with its vintage manufacturing trophies. Willing to forego a single-space typed report, Tom accepted from his pal a set of ¾”- 20 brass nuts, along with the observation “you better have these – every machine in here is going to break down at some point and you’ll need to be able and willing to fix them all.” 19th century millwrights were by then not quite so readily available.

Thirty-five years later Paul made a similar gesture, re-gifting those same industrial accouterments to me after I took over the role of head sawyer, and by default head of maintenance, chief sawdust shoveler, etc. Apart from that short handoff celebration, the ¾”- 20 brass nuts have hung above the sawyer’s stand for the past half century without a day off. Talisman or not, they’ve been there for us, and for that lurking repair.

Operating a hand-set sawmill is hard work. With no hydraulic log turners, automated setworks on the carriage, or even a forklift in those days, Tom and Harry were perpetually sore, but in the best shape of their lives. This provided some perspective on the physicality of the vocation, as both were competitive collegiate wrestlers and Tom the recently retired captain of the US Olympic canoe team at the 1972 Munich games.

Due to the seasonal availability of flowing water, the Garland Mill has always operated from roughly Easter to Thanksgiving, utilizing primarily the Spring snow melt for motive power. The rest of the year is not down time, though Mother Nature puts some constraints on productivity. Winters come early in Coos County, and a generation ago were properly cold and snowy – a few minus 40° F. nights each year to keep the tick population in check. With no sawing to be done in the winter months and mill maintenance a challenge with fingers frozen stiff, other gainful employment was sought by the North Country newcomers. Why not horse logging? Skidders and log trucks balk at getting going in sub-zero conditions but maybe not their equine rivals. Hence that adventure began.

More is to be shared from these halcyon days, including:

- Dealings with local “horse traders”

- The running down of George Smith’s mailbox, not just once

- The overall accounting was not great news for shareholders

Two winters were just about enough. The audacity of a modern-day commercial enterprise to source logs by horse power, then saw out the lumber by water power was barely short of “economic radicalism”.* A physically and financially exhausting scheme, but nonetheless rewarding in a conservationist manner, and a foretaste of such endeavors that the Southworth brothers were capable of.

* A line used about Tom and Harry by Jamie Sayen, shrewd observer and author of Children of the Northern Forest and You Had a Job for Life: The Story of a Company Town.

Tom Southworth with lead horse Dan headed for the log landing in the winter of 1978-79. (Photo: H. Southworth)

Tom’s MBA and Harry’s market research acumen guided the next big offseason trade – draft horses for pigs. Aida and Augustine, two of the finest 500-pound sows to be found in the area made the transition a delight, and only slightly less unprofitable. More to come along these lines:

- Raising and selling piglets; Georgia saving and adopting the runt of the litter

- Needing a stud boar – Major, Major, Major, Major (indeed a reference to Heller’s character but not because he bore any resemblance to Henry Fonda) escaping and being chased around the neighborhood, at last found when local farmer called with the tip off that MMMM was just then perched atop the heap of frozen cow carcasses happily munching away.

Growing up in close proximity to animals and participating in their sustenance and transition from nourishee to nourisher, fostered a compassion and respect for God’s four legged creatures to be found about the place.* Whether intentional or not, this interplay between man, beast, and their natural surroundings also strengthened a spirit of mutual reliance that has remained in all of us. Though much less dramatic than the hardscrabble scenes from Robert Newton Peck’s A Day No Pigs Would Die, “the brutal truths of farm life survival are quite beautiful” as he put it, could be applied to aspects of our childhood in and around the Garland Mill.

* Though work horses and then pigs were the principal animalian co-conspirators around the mill in those days, ducks, chickens, geese and sheep also wandered the grounds from time to time.

Lest we conclude that sawmilling had become a sideshow at the Garland Mill, watching Tom and Harry at work dispelled such a notion. Not only smart and determined, they competed in most all of their tasks – quietly, gentlemanly, and in a production-oriented way. Tom trying to bury his younger brother under a pile of boards to be stacked, offcut slabs to be trimmed and edged, and timbers to be pulled off the carriage and rolled out the back of the mill. Harry, in addition to those tasks of “take away man,” trying to drag enough logs in from the pond to keep his older brother in constant motion rolling the big pines across the deck, fastening to the wood and iron carriage, and sending cant after cant past the saw.

When (first cousins) Ben, McGowan and I started working with our fathers during summer breaks from school, the sawmill mantra the carriage should never stop if the mill is running right was learned and taken as a challenge. The ability of our sires to saw and stack over 2,500 board feet of lumber on a good day was no small feat, and sticks respectfully in my craw when trying to achieve the same with my sons. It doesn’t happen often, and makes me think fondly of Uncle Tom’s line “one boy is worth any two men but two boys aren’t worth a damn.”

Toma and Harry installing new turbine and hydro infrastructure under young Ben’s watchful eye. (1981) (Southworth family photo archives)

McGowan prepping a spruce log for it’s voyage toward the sawmill (1980) (Southworth family photo archives)

Chapter 2 – Learning from Harold and the Old Timers

Tom’s time apprenticing with Harold Alden prior to buying the operation from him was critical to keeping the mill going with any semblance of productivity. It was a crash course in technique and maintenance, and also conditioned his mental state for rendering quality lumber from logs of various size, species and temperament. Harold’s 50 + years running the mill (he sawed on average 150,000 board feet per year, virtually solo), together with the institutional knowledge gained from his father William B. Alden who bought the mill from his boss Eben Garland a generation prior, gave Tom a lot to digest and soon share with his brother.

Harold’s sale of the mill did not mean he’d completely washed his hands of the affair. Yes, he and Lurette traded the home place built and lived in since 1929 for a modest house in the village, but he headed “out East” from time to time to check on Harry and Tom. He dropped hints on setting the correct lead in the saw, how best to prevent the turbine from getting jammed with sticks and leaves in high water, etc. He also made observations as to how the mill was running or rather being run. According to my father Harold showed up an a late-Spring day and stood in the side planer bay quietly watching the afternoon sawing run. Finishing the log on the carriage the new owners idled back the flapping belts and went over to cordially greet their Yankee mentor.

Watercolor painting of the Garland Mill and log pond by Lance Hidy – late 1970s

“You boys must have been sawing big pine this morning” Harold stated in a detached manner. “In fact we were” replied Tom, though having stacked off the pile of 16”, 18” and 20” wide boards sawn before lunch, he and my father were curious about the old timer’s observation. Harold then commented with only a hint of gentle reproach “long chips there in the sawdust shed.” He’d been a spruce and fir sawyer for over half a century and thought sawing wide pine boards was a somewhat frivolous endeavor; but had been curious enough about what the “fellas from away” were doing, to have run his hands through the sawdust pile enroute to the mill. Instead of the short and hard-edged cellulose kernels that normally exit the kerf when the 50” diameter blade is cutting well, Harold found longer, slightly curled pine peelings, indicating that on some cuts the saw blade was completely buried in the log during the cut.

After casting a glance at the water level in the pond, and at the state of affairs on the log deck next to the sawyer’s platform Harold remarked, “not too bad” and headed back out to his old truck. Faint praise, and the end of the afternoon break.

More needs be told about Harold and his East Lancaster orbit:

- Appearance and cat-like dexterity on the logs

- Education through 8th grade (twice) at the Gore School House

- Odd Fellows in the Grange and Lancaster Road Agent

- Tom’s mantra “how would Harold have done this?” back up plan to raw power

- Rivalry with George Placey and Harold’s hedge on rural electrification

The Harold Alden to Tom and Harry Southworth transition at the Garland Mill could easily have been the end of an era of local ownership/operation/residence, but thankfully was not. The situation was not entirely dissimilar to the merchant who lived above the storefront below finally selling out, and the new owner’s incredulity as to how the enterprise could run on fumes for a seeming eternity. Though Tom and Nancy did live above, or at least next to the proverbial storefront, and relished a close to the bone rural existence, they and my folks faced a rather different family economy than Harold and Lurette had. Kids like to eat regularly and even go to town and see a movie on occasion.

Though we’ll delve into the (socio) economics of the adventure in coming chapters, this small vignette from the mid 1930s offers some perspective. A local gentleman who was building a house came to Harold for the framing lumber. Not a palatial affair but nonetheless a house, for which 10-12,000 board feet of planks and boards were needed. A substantial cost now, and one of even greater relative proportion then. After the sizes and quantities of lumber were sorted out, Harold and the client got down to the accounting. The exact cost is no longer known but it was reportedly about double what the customer could pay in cash. Credit was not unheard of, but with scant money in circulation at the time a barter arrangement seemed the practical way forward. What could a mutually valued, or at least accepted medium of exchange be? That particular day it was potatoes—the number of bushels consummating the transaction seemingly not recorded but sufficient for Harold and Lurette to eat a potato dish for breakfast, lunch and dinner for the following six months and the builder to get his wood.

Another lesson learned from Harold on the realpolitik of sawmilling in those days was exemplified in his story told by my father about the repossessed edger. Though I never had the opportunity to corroborate its veracity with Mr. Alden, the only piece of machinery known to depart the Garland Mill’s production lineup and later return to active duty was the edger—a dual-bladed linear sawing machine used to remove the waney/bark edges from planks as they come off the log being sawed. The one in question water-powered via line shaft, flat belt and babbitt bearing, built at Lane Manufacturing in Montpelier, Vermont circa 1880 and still in daily operation.

Scaling logs as they arrive at the mill. 2008 (Photo: Matt Hammon)

In search of all the iron it could lay hands on during WWII, the long arm of the US government reached towards Lancaster, NH. In the early 1940s a gentleman appeared at the mill, pulled several paper-clipped pages from his briefcase and asked Harold if he had on premises an 18” capacity, 2-gang blade, double infeed roll Lane edger. A badge, card or other form of identification may have accompanied the G man’s inquiry, but there was no mention of that (when told the story by my father). The proprietor’s curt, affirmative reply invoked a check mark on one of the pages, then a less than confident query as to which machine it might be – several candidates stared menacingly out of the gloom. A nod past the wooden rollers and carriage track indicated the topic of conversation. Approaching the front end of the edger where the width gauge and “live” blade adjustment arm protruded from the 2,300 pound beast, our visitor slowly and cautiously informed Harold that said item was officially to be requisitioned by the War Department in support of the nation’s martial efforts on two fronts.

A man of few words, and when need be no words at all, Mr. Alden’s shift in posture suggested assent. After several moments of silence and glances from his paperwork to his shoes, then to the edger’s embossed nameplate and back to his papers, the requisitioner mentioned that if the machine was not melted down it would promptly be returned. Possibly a snort of derision from Harold, but certainly a surprised and approving word when the edger was brought back to the Garland Mill in c. 1946. Another check mark made on one of the pages and a signature provided, to say nothing of increased admiration for government record keeping. It was left to the rightful owner to haul the machine back into place and resume operation. The edger has been turning waste wood into usable boards ever since.

As disturbing to a sawmill owner as this story is, albeit with a good end, it piques reflection on the unique nature of the operation. Industrial? Agrarian? Some combination of both? An estimated 55-60 million board feet of lumber has been sawed at the Garland Mill since 1856. Every board foot sawed by harnessing just the power of the water stored behind the 10’ tall dam, then released into a penstock and through the turbine (actually turbines—quite a few different ones over the centuries). The milling process is simultaneously brutal and nuanced. Logs from the pond in front of the mill are corralled with pike pole and steel lasso, then skidded up the submerged ramp and onto the log deck via the bull chain. One, two or as many bodies as may be required then roll the logs onto the Lane #1 carriage using cant dog – stout poles with a steel point and swing hook at the end to capture and help turn the log. The affixed log is carted through the board saw by pulling a lever connected to a friction feed pulley which tensions a flat drive belt (originally leather and now rubberized canvas).

Boards, planks and offcut trimmings fall from the cant as it is whittled down to get to the large dimension timber we now primarily saw in support of timber frame operations. These are pushed, rolled and hauled by hand to the various next steps in the value-adding process. In full and honest disclosure, a small forklift did join the fray about a decade ago to help with the big stock once out of the sawmill. The aforementioned edger does its bit, the Lane 24” planer sizes lumber smoothly but savagely, and the 50’ long run of knee height wooden rollers guide the slabs of various size and shape toward the back of the mill. Boards are pulled aside and stacked with 1” x 1” x 48” long stickers between each course for drying, and the heavy timbers thrust out the postern gate and down the inclined roll case onto the back slip.

One last sharp-edged sentinel lies hidden along the parade of cellulose, the “jump saw”. The 30” diameter blade hums contentedly below the wooden housing, then leaps up to slice through whatever lies atop its deck. Another cleverly engineered tool, the blade is mounted to a long swing arm underneath the mill floor and activated by pushing down with one’s foot a short wooden pedal, thus raising the counter-weighted blade assembly. An upcut trim saw by industry parlance, the jump saw is of similar vintage as all the other machines and is best approached with caution. As my grandmother Hannah found out when helping Dad and Tom saw the few remaining logs for a project back in the early 1980s. A moment of inattention ended her cello career in the Vermont Philharmonic, but quick driving by a local sawdust customer and clever stitching by Doc Quay kept the finger on her hand. Hansy later took up the saxophone and my uncle nailed the bloodied glove to a board just next to the wooden foot-pedal.

Matt Hammon assuredly running slabs across the fabled “jump saw”. (Photo: Fletcher Manley)

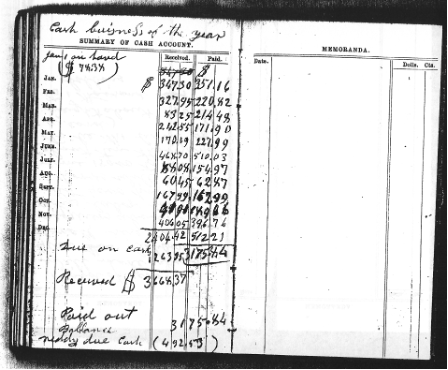

Chapter 2.4 – Eben Garland’s 1866 Diary – are we chronologically egotistical?

Albeit a significant portion of entries devoted to the weather and family health, E. C Garland also recounts in close detail the operation of the mill that year, pivotal in that roughly at this time the Garland Mill upgraded from the “up and down” style reciprocating saw technology it got off the ground using a decade earlier, to state of the art Lane Mfg. circular saw and No. 1 husk and carriage set up.

Accurate and revealing accounting of the day: from “pulling teeth” (25 cents) to “paid help” ($4.50).

As we explore further, it becomes evident that the Garlands and their industrious peers did not sit around much – both in terms of being productive wood-smiths, but also travelling the countryside far and wide. Casual reference to a quick trip to the village (5.25 miles by foot, horse or carriage across dirt tracks then was rather different than by F-150 on smooth asphalt today) was no more normal than a quick trip to Portland, Maine by similar means of transport. Folks on the go.

Chapter 4.2 – Hydro power as harbinger of change

Timber framing and by predictable extension design-build general contracting became in the late 1980s the value adding business model that made it possible for the Southworth brothers to keep the Garland Mill. This model, with various adaptations has sustained the economic status quo for the business and continued to generate enough income to keep up the infrastructure around the sawmill – roofs, dams, foundations don’t tend to repair themselves. Tom and Harry got this ball rolling with great initiative and even more hard work, building a business that their sons could move back home to take part in, ultimately buy, and continue to operate with some success.

The construction company Garland Mill Timberframes grew in stages – creating increasingly inspired, handsome and long-lasting houses, barns, etc.; and weathering the 1st generation business storms – unrelenting long days, chronic under-charging, no health insurance or vacation pay (at least for the owners). The risks and rewards were continually reconciled, and after employees entered the equation, business growth and solidification had to succeed not as a matter of achievement but out of responsibility to the workers and their families earning a paycheck. Swimming effectively in deep water is a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy, but getting out away from shore is a different matter, and mindset.

Tom and Harry swam long and hard. The alternative of sinking, in the form of having to give up the sawmill they revered and put a huge amount of real as well as sweat equity into, didn’t seem to be an option. What was the impetus to jump in this uncharted new direction of post and beam construction with both feet forward and no meaningful experience to guide them? Yes, cash was ever tighter and previous product experimentation hadn’t born much fruit. Yes, Rene Cournoyer their building guru and catalyst for getting into the industry moved to Lancaster at an opportune time (1985) and brought along plenty of tools. Yes, the rising tide of timber framing could possibly have helped lift their little boat, but I doubt they much considered this at the time.

Harry and Tom Southworth rebuilding the hydro generator/turbine room in 2008. (Photo: Dana Southworth)

All these external factors played a role, some more significant than others, in nudging them out into the deeper waters of business. Additionally at play in my estimation were internal factors such as confidence and curiosity. Several years before designing and constructing their 1st timber frame house Harry and Tom envisioned and accomplished a considerable feat – rebuilding the entire water delivery and power generation system at the mill. Simultaneously they installed a small hydro- electric station. I will elaborate on the process and efforts that made this happen, but want to emphasize that this achievement buoyed their spirits and reinforced the notion that achieving difficult, complex projects was in no way out of reach. In short, it helped set the psychological and logistical stage for the next aspect of the adventure.

Hydro power—more than just water over the dam at the Garland Mill. (Photo: Fletcher Manley)

The hydro rebuild took place in the summer/fall of 1982, involving three core elements: design and sitework, fabrication and installation, permitting and funding. Taken alone any one of these would have been seriously prohibitive, in ensemble the perfect cocktail for action…

Other inputs that will be further developed in this part of narrative:

- Mother-in-law and hydro project funder Hannah Jeffery’s wry note on terms

- The Bruce Sloat era of local hydro proliferation in northern NH

- A Solstice party bystander’s cry of “the bridge is collapsing” as the new turbine moved into place

- Ingenuity of the new set up and by consequence better sawing

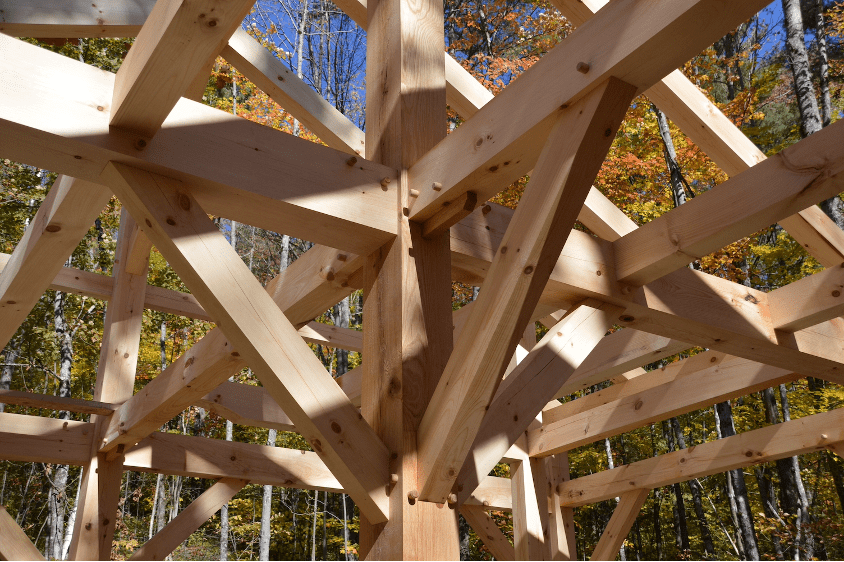

Chapter 4.3 – Timber Framing to the Rescue

Timber framing came as a natural complement to the Mill’s traditional processes, and an economic lifeline to its future. The design and construction of post and beam buildings was added to the mill’s sawing activity in 1986, just about the time Tom and Harry totally ran out of cash. With horse logging and pig farming in the not too distant past and picket fence building just not cutting it, a moderately lucrative change was needed if they were going to be able to keep the mill. The concept of adding value to the lumber being produced made good sense, but the irony of timber framing as a financial savior is laid bare via several jokes within the industry: “How is timber framing like a large pepperoni pizza? It can almost feed a family of four.” and “Timber framing was a plot hatched by Republicans in the late ‘70s to get a bunch of hippies back into the work force.”

(Photo: Fletcher Manley)

Blessing the newly raised frame with “wetting bush” on high and Harry’s special dedication (still reverently read):

As has been the custom for centuries, we attach an evergreen bough to the ridge of the newly raised frame. First, to honor and pay homage to the forest for providing the timbers used in the frame. Second, to bring good fortune to the structure and its owners; and third, to celebrate the community of family and friends who worked together to cut and raise this new building.

Thanks to Nancy’s bookbinding colleague Marnie Cobbs and timberwright Steve Chappell, an opportunity presented itself. Steve’s company Fox Maple was raising a timberframe in Easton, NH close to Marnie’s house and she mentioned to Nancy that Tom and Harry might be interested in the curious and beautiful wooden structure taking shape just down the road. They were, and travelled over to inspect the next day. Steve was only too glad to have a couple more apparently capable (and strong) hands show up just in time for some of the heavier lifting. He invited Dad and Tom to join the crew in raising the rest of the frame. The proverbial light bulbs started to glow. “We can figure this out” said one to another, and they were off and running.

Tom (left) and Harry following up on the hand raising of an apple barn Fall, 1995. (Photo: Fletcher Manley)

Chappell’s talented enthusiasm and the charm of traditional mortise and tenon joinery caught hold of them, as did the notion of developing an in-house value-added product. A handsome product, challenging and fulfilling to make and likely attractive to potential customers. Steve, Tedd Benson, and a number of other visionary builders had rekindled growing interest in the hibernating craft of timber frame construction (their books are captivating). Left somewhat dormant with the advent of dimension lumber (2x4s, 2x6s, etc.) manufacturing and the subsequent rise of conventional “stick frame” construction, the grace and utility of this millennium-old medium was in renaissance. The observation by John Ruskin, 19th century artist, philosopher and architecture critic, that humans take deep and resonant satisfaction in seeing the structure that holds the roof above their heads, is an applicable commentary on the rising popularity of post and beam building. (faintly remembered from school days and roughly paraphrased; I have not yet been able to locate the actual quotation)

Though unaware that an enclave of inspired carpenters employing traditional wood joinery was coalescing in southwest NH in the mid 1980s (the genesis of the Timber Framers Guild), Harry and Tom were just then charting their own course. In collaboration with local architect/builder Alexis Moser, they embarked on a spec house project just outside the village of Lancaster. Tom had worked on Alexis’ winter construction crew when the sawmill was frozen solid. There persisted a mutual respect for work ethic and design, and emboldened by North Country newcomer Rene Courneyer, a skilled studs-to-siding lifelong builder of unusual strength and good humor, the fledgling Garland Mill Timberframes team joined the fray.

Their handsome little story and a half cape showcased fine craftsmanship, super-insulated walls and roof, and a new energy and (post and beam) aesthetic. That house sold quickly in 1987 and has ever since been enjoyed by the same appreciative owner. Big timbers were back on the menu at the Garland Mill and this new aspect of the business was off to a decent start, though briefly interrupted the next year by a fit of log cabin madness.

More to be said about the following aspects of the story…

- Early and long running association with the Timber Framers Guild

- Tooling up with Makita specialty saws, mortisers, etc. brought back from Japan

- From timber frames to full house design/build operations

- Moving out of Tom’s garage and building a proper shop in the abandoned hog pen

- Graph paper and long hand geometry calcs give way to 3 D design software

- Still notching frames almost 40 years on

The warmth and beauty of a GM Timberframes home: unique design, natural materials, lasting construction.

(Photo: Fletcher Manley)

Chapter 5 – Generation X Tests the Waters, and Their Dads

Part 1. “We want to be carpenters, not businessmen.”

Ben, Kirsten and baby Silas moved back from Chile in mid 2002, just as Dana, Izabela and baby David were shipping out to Bosnia. Though positively anticipating the coming field assignment in the Western Balkans, I mused about how delicious it would be to join my cousin, father and uncle in this other vocational venture. The mill and attendant lifestyle continued to beckon. My life as a wandering bureaucrat/foreign servant was in its final stage, unbeknownst to me at that moment, but rather clear when we too moved back to northern New Hampshire in the Autumn of 2004.

International economics and public policy had been a good and intellectually stimulating gig, but departments of state setting our family priorities for us was not going to fly in the long, or even medium term. Plus, I wanted to work with my hands as well as my head, to say nothing of living and raising kids in closer proximity to family. I’d called Dad that spring, inquiring about potential employment at Garland Mill Timberframes and his bifurcated response was enticing: “Well, we’ve already got one of you (Gen X-ers I presumed) back here skulking around, might as well take another…” and “Yes, we have some work and you can start anytime – right at the bottom of the ladder.” Just what was hoped for, and I politely told my bosses that I would unfortunately not be coming back to Washington, or going to Kabul for that matter. Izabela still claims I tricked her into the move but that’s highly unlikely for somebody of my straight-ahead yet simple capabilities; warm and splendid Indian summer in New England did the heavy lifting.

Work commenced directly and the anticipation had not outpaced the blissful and back-sore new reality. A 60% + pay cut was well worth it; the steep learning curve re-engaged the mind and real physical toil chewed off some of the accumulated baby fat. The rural paradise did come with some unexpected, or at least not well-remembered realities such as -40 degree F winter nights (not many) and a scarcity of bakery-fresh bread and the other prized gluten delights of midcontinental Europe. Yet it was remarkably fine, stress free, and unadorned living.

The head sawyer lounging out in front of the mill at break time. (Photo: David Southworth)

Ben’s and my refrain that “we moved back home to be carpenters not businessman” was sung partially tongue in cheek and in relative harmony with our father’s “if we (four headstrong Southworths) want to keep this up, then you probably need to have some skin in the game.” Owning the business was not really what either of us had in mind on the journey back in time toward the future, but it was a logical extension of the current reality. A five-year staged buyout was concocted and agreed upon, and by December, 2010, within days of my father’s unexpected death, Ben and I made the final payment and were owners of Southworth Timberframes, Inc. d.b.a. Garland Mill Timberframes. Lock, stock, barrel and full responsibility. Other than the move to incorporate taken by Harry and Tom a decade prior (to better facilitate the transfer of power if their sons were ever to behave so rashly and romantically), none of this was scripted and likely would have been a flop if choreographed in advance. By the New Year, Tom had unofficially resigned in his wise and wonderful way, though he remained a hugely helpful emeritus carpenter, coach and role model.

Tom Southworth checking planer accuracy on a project with his pal Fletch. (Photo: Fletcher Manley)

Chapter 6 – What’s Next and What’s at Stake?

Part 1. The Relevance of Such an Endeavour.

What’s the relevance of a rather old water-powered sawmill in this era of technologically brilliant yet practically dubious mind games (how truly fulfilling to turn down my freezer temp via “smart phone” whilst careening through the Callahan Tunnel at 86 mph!)? Not much, other than being a relatively key element in our family’s timber framing business. In fact, it’s significantly more than that. Looking at the Garland Mill with 21st century blinders on enhances some aspects of the operation and diminishes others. The continued and revitalized use of that stalwart renewable resource – water, may seem a morally beneficial holdover from decades and centuries past, not to mention a potential cost savings on fuel. That it is, but if not for the continued harnessing of the flowing stream, and only that motive power, this sawmill would likely have gone the way of many others that converted to steam, diesel or electric – ending up in a heap of ashes.

Also, the impounded Garland Brook provides a convenient storage pond for the logs we saw, sometimes a good few years after they get delivered to the mill. Most modern sawmills use sprinkler systems to discourage the bugs from burrowing into the tasty fiber. Our millpond keeps the ants, pine borers, termites, etc. out of the logs, and keeps the tasty fiber soft and easier to saw, especially for a massively underpowered system – about 28 hp peak turbine output, though significantly more torque.

Maneuvering 5000-pound log with a 12’ pike pole and no hydraulics is a feat not even remotely possible unless that log happens to be afloat. With some skill and minimal force, said log is coaxed across the shallow pond and snagged by a loop of chain, then gracefully pulled up the front slip and into the sawmill. It works just as well with smaller logs but this linear infeed method which is parallel with the sawmill and carriage, allows us to saw timbers up to 36’ long, an achievement possible at very few other specialty mills, where they cost a medium-sized fortune.

Big pine logs waltzing up the front slip (white oak inclined plane) and into the mill. (Photo: Matt Hammon)

And speaking of cost, this old mill has saved some nickels over the past 17 decades by sticking with water power. Apart from a few gallons of chain saw gas no fuel has ever been purchased in the milling of approximately 32.5 million board feet of lumber. A pretty decent accumulated carbon credit and even some extra cash for a dinner out with the family from time to time.

Apart from the financial, historic and environmental relevance of this near-extinct modus operendi playing out in the shadow of the northern White Mountains, the Garland Mill has provided jobs for a great many folks to date. It’s no longer quite the industrial beehive seen in the 1860s-1880s when possibly as many as fifty men worked in the various production centers: sawmill, shingle mill, furniture factory, cooperage, maintenance and yard hands, etc. Yet quite a few men and women still show up for meaningful vocational exertion in the mill, timberframe shop, design studio/office and on construction sites.

Work, particularly in the realm of building and creating things, is more than simply clocking in and clocking out. We’ve indulged a human need to make tangible assets since getting up on 2 feet. Some endeavours more striking than others, but covering most of the homo sapiens’ trajectory. Work in and around the Garland Mill has remained physically strenuous yet fulfilling in its character and output(s). Recent additions such as a small forklift and 4 side timber planer (only dating from the 1910s, not 1880s) have eased some of the exertions and bodily abuse, though have not yet diminished the palpable reward from having worked a full, hard day with something you can hold up with your hands to show for it at quitting time.

As we move rapidly away from this tangible vocational mainstay – personally, societally, civilizationally – much of our well-being erodes. Mental illness and physical incapacitation are only the tip of the iceberg we are dancing on. It would be folly, to say nothing of pedantic for me to preach, but I can/should comment on the reality in rural communities such as ours in Coos County, New Hampshire. With the retraction of local manufacturing and agricultural and forest-based industries people are worse off on multiple fronts: economically, inter-personally, and culturally. The century-long migration off the land in the U.S. has supposedly raised the measurable standard of living yet wreaked havoc with the physiology and psychology of many. Not having any connection to, or inkling of where our food comes from, how our shelter is constructed, or why we spend as much time glaring at screens as we do working or sleeping (not to mention talking to each other) are just a few ingredients in the cocktail of misery and likely demise.

More recently, and specifically in northern New England, the closure of almost all the papermills has knocked out a keystone of community well-being, writ large – read Jamie Sayen’s You Had a Job for Life for John McPhee-esque insights into, and demonstratively fine writing on this socio-economic and historical dynamic. Well-intentioned philanthropic organizations have attempted to fill this void with economic assistance, service sector business consulting, variegated “trainings”, and quite a few other salves. They cannot, however, create real and productive jobs in the quantity that will buoy the local community adequately, though practical and focused efforts by groups like the Northern Forest Center are helping in some targeted areas. It’s places like the Garland Mill that can hopefully remain extant and maybe even continue to grow in their small role(s) of helping rural societies rebound.

On such a cautiously optimistic note we charge ahead. With the Garland Mill as vocationally active and diverse in product as it has been over the past century and a half plus, what does the long game look like? Ben’s and my stewardship of the mill in its current iteration of ownership, and leadership of our own building companies (independent of each other since 2020) may have another 10 to 15 years of proverbial steam. Of our 4 nearly grown-up kids, 2 know how to operate the sawmill and work actively in the building trades. David, my older son soon heads off to California as a large-scale construction manager; Robert, his younger brother is lining up studies and an intended subsequent career in international affairs/diplomacy (he’s fully ensconced in the timberframe shop this summer). They might return to the area and family business someday, though it would not be right to either anticipate or encourage that. Tom and Harry did not plan for, and in no way created any expectation for their offspring to boomerang back, and nor do we.

Robert (left) and David Southworth discuss surgery in the timberframe shop (summer 2023) Next generation at the Garland Mill? (Photo: Dana Southworth)

The mill has gone through and re-emerged from a number of modestly radical transitions – ownership, production idioms, and raison d’état. The power plants (turbines) have come and gone but the power (water) has remained constant. A legendary, short-lived steam engine experiment is unofficial and hard to corroborate with available source material, but if truly enacted would likely have overburdened the operational infrastructure and shaken the poor old mill to pieces. The operators and temperament of the place have come and gone, but the need for hard work and innovation has remained constant. What happens next is an open question, but survival of The Garland Mill will necessarily include a new combination of these elemental aspects.

Afterword(s) by Joel McCarty, Friend and Past Executive Director of the Timber Framers Guild

Harry Southworth 1947 – 2010

Timber Framers Guild Member and old pal Harry Southworth put in a day of work on December 20, prepped a birthday cake for one of his grandsons, went to bed, and never woke up. A suggestion that this black event was somehow linked to the lunar eclipse or the solstice would be met by Harry with a derisive snort and his famous grin. He was a couple of weeks shy of his 64th birthday.

Harry Southworth attaching purlins to GM timberframe apple barn September, 1995 (Photo: Fletcher Manley)

There were four Southworth brothers. Three lined up there at the funeral home – all men of substance and accomplishment, cheerily diverse in size, shape, trade, and demeanor. The two we knew showed up early in Guild life and have run long. We retired Harry’s TFG number (317) in the cold database one bright morning last week in view of his presence in the panoramic group photos from Habitat for Humanity (York, Pa., 1989) and the Guelph Bridge project (Ontario, 1992). All I can remember about York is that none of us stopped moving.

In Guelph it was Harry and Tom (and Rick Moyer) who drove cross-county with a van-load of steaming hardwood veneer cores that became the rollers that moved the bridge out over the river in that Pharonic ballet that was our first inkling of the kind of people we might become, or at least be privileged to associate with.

In 1977, Harry and Tom somehow convinced their families to abandon lives of comfort and achievement to buy an 1850s Water-powered sawmill (“No more efficient way to lose money has yet been discovered by modern man”). about as far north in New Hampshire as you can go without needing to speak French every day. Hundreds of us have made the pilgrimage to Garland Mill in the intervening decades; wistful, jealous, and most welcome at the mill, the sauna, the kitchen, and the bonfire. It is impossible to imagine a better place (though we didn’t visit much in the winter).

Harry’s accomplishments included genial support for the Dolly Copp and Russell Colbath projects, spearheading the White Mountain “Terminal Madness” project, and year after year after year of undiluted hospitality and inspiration to crops of Heartwood apprentices in particular and transient TFG members in general.

What we didn’t know about Harry? Two long runs of calling hours at the funeral home were not sufficient to handle the crowds of local folks, each with a story to tell. He played long and hard on the local stage to “favorite fella” reviews-wore a toga in “A Funny Thing Happened…,” sang in the community chorus, played brass in community bands, and served on numerous town boards and committees.

Harry and Cid were married for over 40 years, introduced a fine son (Dana) and daughter (Georgia) into the world, and thereby enjoyed a crop of delightful grandsons David, Robert, Felix, and Casper) – all this in proximity to a community of family and friends so solid and supportive that it ought to give us, from a distance, some comfort.

A good man by any measure. It breaks my heart.

Harry Southworth (right) leads his merry band of timber framers in the GMT shop. (Photo: Dana Southworth)

Tom Southworth 1945 – 2019

Old Pal Tom Southworth died, not unexpectedly, last Saturday night at home. He passed with his family nearby, and with the dignity, warmth, and sense of humor those of us fortunate enough to have known him and his clan will remember for the rest of our years. He was 74.

(Photo: David Tait)

Without irony, Dana Southworth reported back to me this past week that he had just returned from monitoring the current cutting on a 40-acre parcel that Tom and his brother Harry had horse-logged four decades ago, almost to the day.

Also without irony, but perhaps with that grin, Tom explained to me three decades ago that he and Harry went from horse-logging to saw-milling because they were pretty darn sure that they wouldn’t have to walk so much of the up and down (of which New Hampshire has quite a bit), and they could lose money even faster than they had been with that old team of horses, Tom would be the one to make that call, since he had received a degree in economics (Cornell, 1966), all the while whitewater racing canoes at the World Championships level in slalom singles. Packing multiple accomplishments into 1966, he got married too, to this formidable gal he met on the whitewater circuit when they were but teens–Nancy (Abrams), who has been described as a top-notch kayaker, cyclist and skier, homesteader, and Mom, and more.

In 1972, it was off to the Olympics in Munich, Tom at 160lbs and 5’6″, all shoulders and no waist, to compete in canoe slalom doubles (with John Burton) and Nancy in tow and enormously pregnant with Ben. They returned in a hurry, Tom’s hair allegedly still wet from his final Olympic run. The whole world knows what began to unfold in the wee hours of September 5, and the darkness that followed. Tom and Nancy watched it on TV and Ben was born.

With all this accomplishment modestly behind them, somehow they had taken a fancy in their grown-up suburban lives to reading Yankee Magazine (a magazine read by no Yankee ever). This magazine, avidly studied by folks living far South of the Yastrezmski Line, featured traditional recipes, table runner configurations by season, authoritative and important information about period- appropriate wallpaper and drapes, and especially a monthly column called “House For Sale,” featuring some side-road disaster of fading 18th or 19th century charm. Thereby Tom fell for the Garland Mill and bought it, without seeing the inside of the house they would live in and work out of for decades (Worked out,” he reported).

Tom and Nancy and Ben moved up in 1974, McGowan born shortly thereafter (1975). Harry and Cid joined the throng in 1977. What do you suppose it took to abandon the blandishments of the middle class, swapping paychecks and lawns and so forth for the kind of domestic tranquility that has one dipping washing and cooking and bathing water in buckets from a hole in the iced-over mill pond? What did those brothers even to those redoubtable women to get them to turn their backs on lives more comfortable, more “normal” than the one they then faced and embraced up North. I have heard another version of this family lore that has the unflappable Nancy announcing that SHE was moving to the Garland Mill with 2-year-old Ben, and the other three-Tom, Harry, and Cid- could follow as they would care to.

The single strongest and warmest memory of Tom is (one I share with Janet Kane, who can spin a story or two her own self) of a long and languid evening in the “new” house, in a pastoral valley that is likely the only flat spot at that latitude between Maine and the Connecticut River It was an evening abundant with cheery food and drink and conversation, a long slow sunset showing the mountains to the north, south, and cast to good advantage. We enjoyed hours of hilarity and kindness, intellect and empathy. Then up early off the couches for a breakfast reprise, and back to our real lives. What a family!

I had asked nephew Dana for the inside story on Tom’s character, which we all found formidable, thoroughly modest, and unfailingly kind but still a bit of a mystery for all that. “Tom had strength of character even greater than that of body and mind. Integrity with a capital I and his patience and genuine delight in working with those around him regardless of size, shape, or ability was real. More than just a sense of humor and optimism, Tom made those who spent any time at all in his company feel better about themselves and the world, though sometimes not the wall we might, be re-framing. He was about the most fair-minded person I’ve known–a real stickler in this regard, from running the Lancaster planning board through real headwinds, to playing every kid on the little league team (even me), to dealing with employees, contractors, suppliers, and even cantankerous clients. He led by example, at work, at home, at play, and at the dinner table. (Tom claims that only Doug Lukian could out-eat him!)”

Characteristically, Tom did not see fit to mention to me his dire straits in our final digital communications just a couple of days before he died. He was more interested in pursuing a tale told long ago by my own dad about his decision to enter the ministry directly from a minor league baseball career, upon facing his first series of major league inside curves. We chatted a bit about spring training, and that was it.

Gratitude is the only remedy for grief, and it is seriously incomplete and comes on all too slowly, but it comes on, and lasts as long as we do. So raise your glasses, ladies and gentlemen, to a man without equal in our time.

The Garland Mill (1856 – 2024) – Timeline & Synopsis (cit. local newspapers, Lancaster Historical Society)

1856 Eben C. Garland (1817-1891) builds the Garland Mill in Lancaster, NH on Garland Brook channel

c.1865 The Garland Mill converted from sash saw technology to Lane Mfg. circular saw and other equipment

1870 Concord & Montreal RR extended to Lancaster (vast increase in log and lumber exports from N. NH)

c.1872 Garland’s Chair Manufactory built on grounds, major value-adding aspect of operation

c.1875 Eben Garland involves son George as partner in growing business named E.C. Garland & Son

1877 Furniture factory known locally as the “bedstead manufactory” destroyed by fire, not rebuilt

c.1880 Peak production of the mill–over 450,000 board feet of sawn lumber, 100,000 shingles, furniture, etc.

1884/6 William B. Alden buys the mill from the Garlands; George and Charles Garland move to Tennessee

1887 Kilkenny RR logging line to the headwaters of the Garland Brook, by 1897 all timber had been logged off

1887 Wm. Alden buys two local farms (Truland and Connary), develops large scale agriculture (post timber era)

1891 Eben C. Garland (age 75) and his son George Garland (41) die, the latter after move to Chattanooga, TN

1926 Harold Alden buys the mill from his father William B. Alden, and runs operation by himself for 47 years

1944 William B. Alden (age 90) died and was buried in Summer St. cemetery in Lancaster

1974 Tom and Nancy Southworth buy the Garland Mill from Harold Alden, move north from Philadelphia

1977 Harry and Cid Southworth come to Lancaster, NH (from PA) – Harry joins brother Tom in business

1982 Southworths install an S. Morgan Smith turbine (c. 1934) with new penstock, wheelpit, and small hydro

1983 The Garland Mill listed in the National Register of Historic Places

1986 Garland Mill Timberframes (GMT) founded as in-house building company to augment sawing activity

1989 Tom and Harry join the Timber Framer’s Guild, host numerous Guild projects at the mill over the years

1995 Harold B. Alden (age 94) died and was buried in Summer St. cemetery in Lancaster

2002 Ben Southworth returns to Lancaster (from Chiloe, Chile) and joins GMT operations

2004 Dana Southworth returns to Lancaster (from Sarajevo, Bosnia) and joins GMT operations

2006 Dana and Ben begin 5-year buyout of Garland Mill from fathers Harry and Tom

2007 Furniture making re-introduced on limited scale to mill’s product offering (Garland Joinery by name)

2010 Harry Southworth dies (age 63); Dana and Ben complete purchase of Garland Mill from fathers

2017 D. Southworth and Seth and Luke Colby rebuild full sawmill carriage track (last done in 1880s)

2019 Tom Southworth dies peacefully at home (age 74), within a few stones throws of the mill

2020 3rd generation Southworths, David and Robert, actively involved in sawmilling and timber framing

2022 GMT builds its largest full timberframe structure to date (pine and cherry) for a 2nd gen. client

2024 Another Timber Framer’s Guild Rendezvous hosted at The Garland Mill to work, learn and celebrate

~ An estimated 32,500,000 board feet of timber and lumber sawn by water power over the past 168 years. ~

Cast of Characters and Willing Accomplices

Potential corroborators/critics on this tale – good-humored and clear-headed folks!

1. David Craxton, “The Long View” – 50-year perspective on the mill and GMT

• Tom’s first employee in 1974, fine builder, extraordinary farmer/organic grower

• Friend from the mists of time and participant in many Garland timberframe raisings

• Patient client – GMT built barn for Dave and Andrea in 2018 (photo on page 21)

2. Matt Hammon, “The Insider” – worked with Tom, Harry, Ben, Dana since 2006

• Knows the mill very well from operational as well as historical perspectives

• Nuanced spokesman for sawmilling/timberframing/building aspects

• Carpenter, foreman, timber framer, production manager

3. Seth and Luke Colby, unofficial CTOs (chief technical officers) & timber framing experts

• Directly involved in every major infrastructure project at the mill since 2008

• Key players in the most challenging Garland Mill Timberframes projects since 2008

• Electricians, builders, mechanics, modern Renaissance men

4. Fletcher Manley, Chronicler of sawmilling, timberframing, and so much more

• Top notch photographer of worldwide focus and accolade

• Participant in many building endeavors, including his and Harriet’s house

• Focal point of Southworth family’s multi-generational admiration and gratitude

5. Joel McCarty, fine friend and former President and E.D. of the Timber Framer’s Guild

• Eloquent pal and co-conspirator of Tom and Harry since the early days of TFG

• With wife Susan dedicated a good portion of life to improving our timber trade

6. Trevor Downing, 3rd generation Northeast Kingdom logger and lumberman

• With his father, uncle, grandfather, great-uncle have been supplying top quality saw logs to the Garland Mill for the past 45 + years; they’re just getting warming up…

7. Chris Barstow (Specialty Timberworks) and Kyle Whitehead (Mink Hill Timberframes), “Veteran Voices” of the industry and great friends and allies

• Excellent practitioners and experts in frame design, joinery, raisings – the real deal

• Long time professional and pro-bono project collaboration with GMT (and TFG)

8. Georgia and McGowan Southworth, the wise and supportive Siblings in NYC

• Witness to most of the current era Garland Mill madness & mayhem

9. John (Sandy) Pike, clear-headed client and patron

• 2nd generation timberframe home customer of 2nd generation GMT stewards

• Enthusiastic participant in milling timbers for his own frame(s)

An incomplete and growing list…many others of equal valor thought of, if not mentioned.

Coos County Democrat newspaper article by John Harrigan in May, 1983

FROM TREE TO TIMBERFRAME A Photo Essay by Fletcher Manley

Timber framing came as a natural complement to the mill’s traditional processes. The design and construction of post and beam buildings was added to the mill’s sawing activity in 1986. More than a century earlier The Garland Mill provided heavy timbers for local builders who routinely used mortise and tenon joinery in their construction. Today the mill saws timbers from native species to meet the needs of our building company.

Wrestling a big pine into the sawmill. No hydraulics.

Sawmilling 19th century style on a hand-set Lane No. 1 (made in Montpelier, Vermont c. 1880).

The next generation flexes its muscles. Turning the cant.

The layout and notching have remained true to the craft since timber framing operations began at the mill over thirty-five years ago—traditional mortise and tenon joinery cut by hand, one frame at a time in the shop. Eastern white pine, red oak, cedar, hemlock, cherry, spruce & fir – some of the wood species milled and fashioned into lasting structures in the GMT shop.

Traditional timber joinery fastened with oak pegs.